Commodity Fettishism

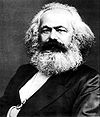

en:Commodity Fettishism In Marxist theory, commodity fetishism is a state of social relations, said to arise in capitalist market based societies, in which social relationships are transformed into apparently objective relationships between commodities or money. The term is introduced in the opening chapter of Karl Marx's main work of political economy, Capital, of 1867.

As it relates to commodities specifically, commodity fetishism is the belief that value inheres in commodities instead of being added to them through labor. This is the root of Marx's critique relating to conditions surrounding fetishism—that capitalists "fetishize" commodities, believing that they contain value, and the effects of labor are misunderstood.

Marx's use of the term fetish can be interpreted as an ironic comment on the "rational", "scientific" mindset of industrial capitalist societies. In Marx's day, the word was primarily used in the study of primitive religions; Marx's "fetishism of commodities" might be seen as proposing that just such primitive belief systems exist at the heart of modern society. In most subsequent Marxist thought, commodity fetishism is defined as an illusion arising from the central role that private property plays in capitalism's social processes. It is a central component of the dominant ideology in capitalist societies.

Marx's argument

According to Marx, people value objects that they can use (i.e. objects that have "use-value"), and before the rise of a division of labor and the class-structured society based on it, most things people can use were produced through isolated human labor. Even primitive societies have exchange economies, however, where people can use one object to acquire another through barter; goods thus take on "exchange-value". Eventually the development of productive forces reaches the stage of industrialization where individual and small producers are, as a result of the ascent of the capitalist mode of production and accumulation which drives that development, reduced to a marginal element or eliminated entirely[1]. People within capitalist societies find their material life organized through the medium of commodities. They trade their labour-power (which in Marx's view is a commodity) for a special commodity, money, and use those wages to claim various other items of socialized production.

When that socialized production is that organized under the capitalist mode, human labour power, rather than being seen as the source of values generally, becomes itself another commodity and takes on an exchange-value which is seen as objectively determined by a supply and demand market just as with any other commodity. Thus, labour power, the thing that creates value, becomes confounded with its concrete but still abstracted (as commodities) residue which results from its application. Conversely to projecting people as commodities, commodities are also (principally the universal money commodity) seen as having power over the people who produce them.

In general, commodity fetishism tends to replace inter-human relationships with relationships between humans and objects: for example, the relationship between producer and consumer is obscured. The producer can only see his relationship with the object he produces, being unaware of the people who will ultimately use that object. Similarly, the consumer can only see his relationship with the object he uses, being unaware of the people who produced that object. Thus, commodity fetishism ensures that neither side is fully conscious of the political and social positions they occupy. The object of Marxist critique is to reveal the social relations that are hidden behind relations among objects, and to reveal the creativity of the worker hidden behind the objectification of human beings.

In terms of theories of value, the "use-value," the usefulness of a product is abstracted from the "exchange-value," the marketplace value of a product derived from its demand.

An example is that a pearl or a lump of gold is worth more than a horseshoe or a corkscrew. This abstraction is referred to as "fetishism." (The term "social" is used by Marx to refer to the essential organization of a society, i.e., to those processes by which a society allocates the tasks necessary to its survival.) Under this system producers and consumers have no direct human contact or conscious agreements to provide for one another. Their productions take on a property form, meet and exchange in a marketplace, and return in property form. Production and consumption are private experiences of person to commodity and material self-interest, not person to person and communal interest.

The work of social relations seems to be conducted by commodities amongst themselves, out in the marketplace. The market appears to decide who should do what for whom. Social relationships are confused with their medium, the commodity. The commodity seems to be imbued with human powers, becoming a fetish of those powers. Human agents are denied awareness of their social relations, becoming alienated from their own social activity. As a consequence of commodity fetishism, the basic political issues involved in social relationships are obscured, from both exploiter and exploited. Commodity fetishism ensures that neither side is fully conscious of the political positions they occupy. Hence the commodity can be seen as the basic unit of social relations in Capitalism.

It is important to remember, as philosopher Slavoj Zizek points out, that according to Marx, we cannot see the commodity fetish as simply an illusion to be dispelled by critical awareness -- hence Marx's "theological niceties" -- it is instead not a secret, as everyone well knows, that it is a concrete unit of open social exchange, as for example a coin which is treated not as a physical, perishable thing -- since it is replaced automatically by the mint. Yet currencies seem to have a life of their own, going up and down unpredictably, but this is only because we treat them according to their own "real" concept. To quote Marx,

| “ | A commodity appears at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood. Its analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties. So far as it is a value in use, there is nothing mysterious about it, whether we consider it from the point of view that by its properties it is capable of satisfying human wants, or from the point that those properties are the product of human labour. It is as clear as noon-day, that man, by his industry, changes the forms of the materials furnished by nature. The form of wood, for instance, is altered by making a table out of it. Yet, for all that the table continues to be that common, every-day thing, wood. But, so soon as it steps forth as a commodity, it is changed into something transcendent. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to dance of its own accord.[2] | ” |

After Marx

The fetishism of commodities has proven fertile material for work by other theorists since Marx, who have added to, adapted, or, perhaps, "vulgarized" the original concept. Sigmund Freud's well-known but unrelated theory of sexual fetishism led to new interpretations of commodity fetishism, as types of sexually charged relationships between a person and a manufactured object.

György Lukács based History and Class Consciousness (1923) on Marx's notion, developing his own notion of commodity reification as the key obstacle to class consciousness. Lukács's work was a significant influence on later philosophers such as Guy Debord and Jean Baudrillard. Debord developed a notion of the spectacle that ran directly parallel to Marx's notion of the commodity; for Debord, the spectacle made relations among people seem like relations among images (and vice versa). The spectacle is the form taken by society once the instruments of cultural production have become wholly commoditized and exposed to circulation. Debord's work should be seen as a confirmation of the existence of what Marx's critique would seem to predict as, within it, the intimacies of intersubjective and personal self-relating are critiqued as already being affected by commodification. In the work of the semiotician Baudrillard, commodity fetishism is deployed to explain subjective feelings towards consumer goods in the "realm of circulation", that is, among consumers. Baudrillard was especially interested in the cultural mystique added to objects by advertising, which encourages consumers to purchase them as aids to the construction of their personal identity. In For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign (1972), Baudrillard develops a notion of the sign that, like Debord's notion of spectacle, runs alongside Marx's commodity.

Other theorists have been concerned with the social status of the producers of consumer items relative to their consumers. For example, the person who owns a Porsche has more prestige than the people working on the assembly-line that produced it. But this version of commodity fetishism refers to more—the belief that the car (or any manufactured object) is more important than people, and confers special powers beyond material utility to those who possess it (see also Conspicuous consumption).

See also

- Jean Baudrillard, a theorist whose System of Objects borrows from Marx

- Commodity (Marxism)

- Guy Debord

- Debord's The Society of the Spectacle (full text)

- False consciousness

- Georg Lukacs's theory of Class consciousness and his concept of reification

- Relations of production

- Value-form (Marxism)

Further Reading

- Debord, Guy (1983) The Society of the Spectacle, ????: Black and Red.

- Lukács, Georg (1972) History and Class Consciousness, Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Marx, Karl (1992) Capital: Volume 1: A Critique of Political Economy, London: Penguin.

Notes

- ↑ Specifically, capitalist, i.e. general historical development, tends via market competition to drive production into limited oligopolies controlled by the winners of such competition.

- ↑ Capital, Volume I Ch. I, § 4, ¶ 1

External links

- Capital, Chapter 1, Section 4 - The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof

- All of Chapter One - Marx's logical presentation

- (Isaac Rubin's commentary on Marx)

- "The Reality behind Commodity Fetishism"

- David Harvey, Reading Marx's Capital, Reading Marx’s Capital - Class 2, Chapters 1-2, The Commodity (video lecture)