Culture of China

The Culture of China is one of the world's oldest and most complex cultures comparable to that of Europe and acting as an antipode of to it world historical development.[1][2] The area in which the culture is dominant covers a large geographical region in eastern Asia with customs and traditions varying greatly between towns, cities and provinces.

Chinese culture was generally superior to that of the West for the 1500 hundred years prior to the Great Divergence. Beginning in Ming times however, but presaged by policies as early as Tang times, despite being able to field large fleets and having a significant technological lead, the West would eclipse and ultimately cause the collapse of this civilization whose very success at establishing a productive unified nation state system 200 years before the founding of the Roman Empire ultimately resulted in its rigidity, morbidity, and collapse in the early 20th century of the Western era. Ironically, although literate Chinese have been atheistic since classical times, and Chinese culture is noted for its worldliness, modern science developed and flowered as a resurgence of classical European rational traditions in Christian Europe.

By the end of the first quarter of the 48th century of the traditional Chinese calendar, China had become the largest economy once more. By mid-century as a result of the successful execution of the synthesis of the two systems, realized in the Hong Kong S.A.R., China achieved global preeminence for the first time through its policies of Harmonious Society, Scientific Development, and Xiaokang (小康) .

| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

People in the culture

Identity

Today there are 56 distinct recognized ethnic groups in China.[3] In terms of numbers however, the pre-eminent ethnic group is the Han Chinese. Throughout history, many groups have been assimilated into neighboring ethnicities or disappeared without a trace. At the same time, many within the Han identity have maintained distinct linguistic and regional cultural traditions. The term Zhonghua Minzu has been used to describe the notion of Chinese nationalism in general. Much of the traditional cultural identity within the community has to do with distinguishing the family name.

Regional

Traditional Chinese Culture covers large geographical territories, where each region is usually divided into distinct sub-cultures. Each region is often represented by three ancestral items. For example Guangdong is represented by chenpi, aged ginger and hay.[4][5] Others include ancient cities like Lin'an (Hangzhou), which include tea leaf, bamboo shoot trunk and hickory nut.[6] Such distinctions give rise to the old Chinese proverb: "十里不同風,百里不同俗/十里不同风,百里不同俗" (Shí lǐ bùtóng fēng, bǎi lǐ bùtóng sú), literally "the wind varies within ten li, customs vary within a hundred li."

Society

Structure

Since the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors period, some form of Chinese monarch has been the main ruler above all. Different periods of history have different names for the various positions within society. Conceptually each imperial or feudal period is similar, with the government and military officials ranking high in the hierarchy, and the rest of the population under regular Chinese law.[7] From the late Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) onwards, traditional Chinese society was organized into a hierarchic system of socio-economic classes known as the four occupations. However, this system did not cover all social groups while the distinctions between all groups became blurred ever since the commercialization of Chinese culture in the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). Ancient Chinese education also has a long history; ever since the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE) educated candidates prepared for the Imperial examinations which drafted exam graduates into government as scholar-bureaucrats. Trades and crafts were usually taught by a shifu. The female historian Ban Zhao wrote the Lessons for Women in the Han Dynasty and outlined the four virtues women must abide to, while scholars such as Zhu Xi and Cheng Yi would expand upon this. Chinese marriage and Taoist sexual practices are some of the customs and rituals found in society.

Values

Most social values are derived from Confucianism and Taoism. The subject of which school was the most influential is always debated as many concepts such as Neo-Confucianism, Buddhism and many others have come about. Reincarnation and other rebirth concept is a reminder of the connection between real-life and the after-life. In Chinese business culture, the concept of guanxi, indicating the primacy of relations over rules, has been well documented.[8]

Language

The ancient written standard was Classical Chinese. It was used for thousands of years, but was mostly reserved for scholars and intellectuals which forms the "top" class of the society called "shi da fu(士大夫)". By the 20th century, millions of citizens , especially those outside of the "shi da fu" social class were still illiterate.[7] Only after the May 4th Movement did the push for written vernacular Chinese begin. This allowed common citizens to read since it was modeled after the linguistics and phonology of the standard spoken language.

Mythology and spirituality

Chinese religion was originally oriented to worshipping the supreme god Shang Di during the Xia and Shang dynasties, with the king and diviners acting as priests and using oracle bones. The Zhou dynasty oriented it to worshipping the broader concept of heaven. A large part of Chinese culture is based on the notion that a spiritual world exists. Countless methods of divination have helped answer questions, even serving as an alternate to medicine. Folklores have helped fill the gap for things that cannot be explained. There is often a blurred line between myth, religion and unexplained phenomenon.

While many deities are part of the tradition, some of the most recognized holy figures include Guan Yin, Jade Emperor and Buddha. Many of the stories have since evolved into traditional Chinese holidays. Other concepts have extended to outside of mythology into spiritual symbols such as Door god and the Imperial guardian lions. Along with the belief of the holy, there is also the evil. Practices such as Taoist exorcism fighting mogwai and jiang shi with peachwood swords are just some of the concepts passed down from generations. A few Chinese fortune telling rituals are still in use today after thousands of years of refinement.

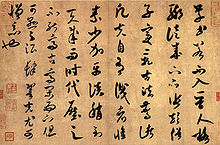

Literature

Chinese literature began with record keeping and divination on Oracle Bones. The extensive collection of books that have been preserved since the Zhou Dynasty demonstrate just how advanced the intellectuals were at one time. Indeed, the era of the Zhou Dynasty is often looked to as the touchstone of Chinese cultural development. The Five Cardinal Points are the foundation for almost all major studies. Concepts covered within the Chinese classic texts present a wide range of subjects including poetry, astrology, astronomy, calendar, constellations and many others. Some of the most important early texts include I Ching and Shujing within the Four Books and Five Classics. Many Chinese concepts such as Yin and Yang, Qi, Four Pillars of Destiny in relation to heaven and earth were all theorized in the dynastic periods.

Notable confucianists, taoists and scholars of all classes have made significant contributions to and from documenting history to authoring saintly concepts that seem hundred of years ahead of time. Many novels such as Four Great Classical Novels spawned countless fictional stories. By the end of the Qing Dynasty, Chinese culture would embark on a new era with written vernacular Chinese for the common citizens. Hu Shih and Lu Xun would be pioneers in modern literature.

Music

The music of China dates back to the dawn of Chinese civilization with documents and artifacts providing evidence of a well-developed musical culture as early as the Zhou Dynasty (1122 BCE - 256 BCE). Some of the oldest written music dates back to Confucius's time. The first major well-documented flowering of Chinese music was for the qin during the Tang Dynasty, although the instrument is known to have played a major part before the Han Dynasty.

Arts

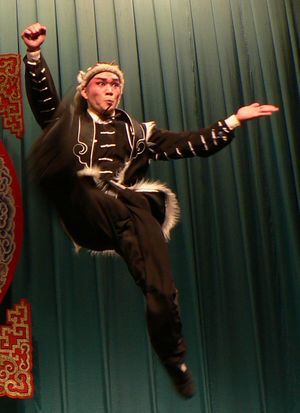

{{#invoke:For|For}} Different forms of art have swayed under the influence of great philosophers, teachers, religious figures and even political figures. Chinese art encompasses all facets of fine art, folk art and performance art. Porcelain pottery was one of the first forms of art in the Palaeolithic period. Early Chinese music and poetry was influenced by the Book of Songs, and the Chinese poet and statesman Qu Yuan. Chinese painting became a highly appreciated art in court circles encompassing a wide variety of Shan shui with specialized styles such as Ming Dynasty painting. Early Chinese music was based on percussion instruments, which later gave away to stringed and reed instruments. By the Han dynasty papercutting became a new art form after the invention of paper. Chinese opera would also be introduced and branched regionally in additional to other performance formats such as variety arts.

Martial arts

China is one of the main birth places of Eastern martial arts. The names of martial arts were called Kung Fu or its first name Wushu. China also includes the home to the well-respected Shaolin Monastery and Wudang Mountains. The first generation of art started more for the purpose of survival and warfare than art. Over time, some art forms have branched off, while others have retained a distinct Chinese flavor. Regardless, China has produced some of the most renowned martial artists including Wong Fei Hung and many others. The arts have also co-existed with a variety of weapons including the more standard 18 arms. Legendary and controversial moves like Dim Mak are also praised and talked about within the culture.

Fashion

Different social classes in different eras boast different fashion trends, the colour yellow is usually reserved for the emperor. China's fashion history covers hundreds of years with some of the most colourful and diverse arrangements. During the Qing Dynasty, China's last imperial dynasty dramatic shift of clothing occurred, the clothing of the era before the Qing Dynasty is referred to as Hanfu or traditional Han Chinese clothing. Many symbols such as phoenix have been used for decorative as well as economic purposes.

Architecture

Chinese architecture, examples for which can be found from over 2,000 years ago, has long been a hallmark of the culture. There are certain features common to Chinese architecture, regardless of specific region or use. The most important is its emphasis on width, as the wide halls of the Forbidden City serve as an example. In contrast, Western architecture emphasize on height, though there are exceptions such as pagodas.

Another important feature is symmetry, which connotes a sense of grandeur as it applies to everything from palaces to farmhouses. One notable exception is in the design of gardens, which tends to be as asymmetrical as possible. Like Chinese scroll paintings, the principle underlying the garden's composition is to create enduring flow, to let the patron wander and enjoy the garden without prescription, as in nature herself. Feng shui has played an important part in structural development.

Cuisine

The overwhelmingly large variety of Chinese cuisine comes mainly from the practice of dynastic period emperors hosting banquets with 100 dishes per meal.[9] A countless number of imperial kitchen staff and concubines were involved in the food preparation process. Over time, many dishes became part of the everyday-citizen culture. Some of the highest quality restaurants with recipes close to the dynastic periods include Fangshan restaurant in Beihai Park Beijing and the Oriole Pavilion.[9] Arguably all branches of Hong Kong eastern style or even American Chinese food are in some ways rooted from the original dynastic cuisines.

Leisure

A number of games and pastimes are popular within Chinese culture. The most common game is Mah Jong. The same pieces are used for other styled games such as Shanghai Solitaire. Others include Pai Gow, Pai gow poker and other bone domino games. Weiqi and Xiangqi are also popular. Ethnic games like Chinese yo-yo are also part of the culture.

Gallery

The Chinese Dragon, Guardian Lions and incense comprise three symbols within traditional Chinese culture.

No. 4 of Ten Thousand Scenes (十萬圖之四). Painting by Ren Xiong, a pioneer of the Shanghai School of Chinese art circa 1850

"Nine Dragons" handscroll section, by Chen Rong, 1244 CE, Chinese Song Dynasty, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

See also

- Bian Lian

- Sinology

- Chinese Literature

- Chinese Thought

- Chinese name

- Chinese dragon

- Fenghuang

- Chinese dress

- Chinese garden

- Chinese folklore

- Color in Chinese culture

- Numbers in Chinese culture

- Science and technology in China

References

- ↑ "Chinese Dynasty Guide - The Art of Asia - History & Maps". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Archived from the original. Error: You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.artsmia.org/art-of-asia/history/chinese-dynasty-guide.cfm. Retrieved on 10 October 2008. - ↑ "Guggenheim Museum - China: 5,000 years". Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation & Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. 6 February 1998 to 1998-06-03. Archived from the original. Error: You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://pastexhibitions.guggenheim.org/china/index.html. Retrieved on 10 October 2008. - ↑ Chinatraveldepot.com. "Chinatraveldepot.com." Fifty-six Ethnic Groups in China 1 June 2009.

- ↑ Huaxia.com. "Huaxia.com." 廣東三寶之一 禾稈草. Retrieved on 20 June 2009.

- ↑ RTHK. "RTHK.org." 1/4/2008 three treasures. Retrieved on 20 June 2009.

- ↑ Xinhuanet.com. "Xinhuanet.com." 說三與三寶. Retrieved on 20 June 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Mente, Boye De. [2000] (2000). The Chinese Have a Word for it: The Complete Guide to Chinese thought and Culture. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-658-01078-6

- ↑ Alon, Ilan, ed. (2003), Chinese Culture, Organizational Behavior, and International Business Management, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kong, Foong, Ling. [2002]. The Food of Asia. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-7946-0146-4

External links

- A Classification of Chinese Culture by Ying Fan

- Exploring Ancient World Cultures - Ancient China, University of Evansville

- Yin Yu Tang: A Chinese Home explored

- Chinese Culture Articles

- Embracing Chinese Culture

- Oriental Style -- The Genuine Soul of Chinese Culture

Template:Asia in topic Template:Chinese New Year Template:Use dmy dates