Revolution: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[:en:Revolution]] | [[:en:Revolution]] | ||

[[File:Maquina vapor Watt ETSIIM.jpg|left|thumb|''''"Revolutions are the locomotives of history"''' - ''Karl Marx'']] | |||

{{TOCright}} | |||

<div> | |||

A '''revolution''' (from the [[Vulgar Latin|Latin]] ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental [[social change|change]] in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time. | A '''revolution''' (from the [[Vulgar Latin|Latin]] ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental [[social change|change]] in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time. | ||

[[Aristotle]] described two types of political revolution: | [[Aristotle]] described two types of political revolution: | ||

# Complete change from one constitution to another | <html><div style="position: relative; left: 100px;"></html> | ||

# Modification of an existing constitution.<ref>Aristotle, ''The Politics'' V, tr. T.A. Sinclair (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964, 1972), p. 190.</ref> | #Complete change from one constitution to another | ||

#Modification of an existing constitution.<ref>Aristotle, ''The Politics'' V, tr. T.A. Sinclair (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964, 1972), p. 190.</ref> | |||

<html></div></html> | |||

Revolutions have occurred through [[human history]] and vary widely in terms of methods, duration, and motivating [[ideology]]. Their results include major changes in [[culture]], [[economy]], and [[social institution|socio]]-[[political institution]]s. | Revolutions have occurred through [[human history]] and vary widely in terms of methods, duration, and motivating [[ideology]]. Their results include major changes in [[culture]], [[economy]], and [[social institution|socio]]-[[political institution]]s. | ||

Scholarly debates about what does and does not constitute a revolution center around several issues. Early studies of revolutions primarily analyzed events in [[European history]] from a [[psychological]] perspective, but more modern examinations include global events and incorporate perspectives from several [[social science]]s, including [[sociology]] and [[political science]]. Several generations of scholarly thought on revolutions have generated many competing theories and contributed much to the current understanding of this complex phenomenon. | Scholarly debates about what does and does not constitute a revolution center around several issues. Early studies of revolutions primarily analyzed events in [[European history]] from a [[psychological]] perspective, but more modern examinations include global events and incorporate perspectives from several [[social science]]s, including [[sociology]] and [[political science]]. Several generations of scholarly thought on revolutions have generated many competing theories and contributed much to the current understanding of this complex phenomenon. | ||

</div> | |||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

[[Copernicus]] named his 1543 treatise on the movements of planets around the sun ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (''On the Revolutions of Celestial Bodies'') and this has come to be the model type of a [[scientific revolution]]. However "Revolution" is attested by at least 1450 in the sense of representing abrupt change in a [[social order]]<ref>[[Oxford English Dictionary|OED]] vol Q-R p. 617 1979 Sense III states a usage "Alteration, change, mutation" from 1400 but lists it as "rare". "c. 1450, Lydg 1196 ''Secrees'' of Elementys the Revoluciuons, Chaung of tymes and Complexiouns." It's clear that the usage had been established by the early 15th century but only came into common use in the late 17th in England. </ref><ref>[http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=revolution onlineetymology.com ]</ref>. Political usage of the term had been well established by 1688 in the description of the replacement of [[James II of England|James II]] with [[William III of Orange|William III]]. The process was termed ''"[[The Glorious Revolution]]"''.<ref>Richard Pipes, ''[http://chagala.com/russia/pipes.htm A Concise History of the Russian Revolution]''</ref> Apparently the sense of social change and the geometric sense as in "[[Surface of revolution]]" developed in various European languages from the [[Latin]] between the 14th and 17th centuries, the former developing as a metaphor from the latter. "Revolt" as an event designation appears after the process term and is given a related but distinct and later derivation. | [[Copernicus]] named his 1543 treatise on the movements of planets around the sun ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (''On the Revolutions of Celestial Bodies'') and this has come to be the model type of a [[scientific revolution]]. However "Revolution" is attested by at least 1450 in the sense of representing abrupt change in a [[social order]]<ref>[[Oxford English Dictionary|OED]] vol Q-R p. 617 1979 Sense III states a usage "Alteration, change, mutation" from 1400 but lists it as "rare". "c. 1450, Lydg 1196 ''Secrees'' of Elementys the Revoluciuons, Chaung of tymes and Complexiouns." It's clear that the usage had been established by the early 15th century but only came into common use in the late 17th in England. </ref><ref>[http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=revolution onlineetymology.com ]</ref>. Political usage of the term had been well established by 1688 in the description of the replacement of [[James II of England|James II]] with [[William III of Orange|William III]]. The process was termed ''"[[The Glorious Revolution]]"''.<ref>Richard Pipes, ''[http://chagala.com/russia/pipes.htm A Concise History of the Russian Revolution]''</ref> Apparently the sense of social change and the geometric sense as in "[[Surface of revolution]]" developed in various European languages from the [[Latin]] between the 14th and 17th centuries, the former developing as a metaphor from the latter. "Revolt" as an event designation appears after the process term and is given a related but distinct and later derivation. | ||

==Types== | ==Types== | ||

[[File: | [[File:Prise de la Bastille.jpg|left|thumb|The [[storming of the Bastille]], 14 July 1789 during the [[French Revolution]].]] | ||

There are many different typologies of revolutions in social science and literature. For example, classical scholar [[Alexis de Tocqueville]] differentiated<ref>Roger Boesche, ''Tocqueville's Road Map: Methodology, Liberalism, Revolution, and Despotism'', Lexington Books, 2006, ISBN 0739116657, [http://books.google.com/books?id=fLL6Bil2gtcC&pg=PA86&dq=%22types+of+revolution%22&as_brr=3&ei=hdVQR6TVIpm4pgLFvJ2fBw&sig=ZEc373JU8-9qM9N4BgKjnvvHVD8#PPA86,M1 Google Print, p.86]</ref> between 1) [[political revolution]]s 2) sudden and violent revolutions that seek not only to establish a new political system but to transform an entire society and 3) slow but sweeping transformations of the entire society that take several generations to bring about (ex. [[religion]]). One of several different [[Marxist]] typologies divides revolutions into pre-capitalist, early bourgeois, bourgeois, bourgeois-democratic, early proletarian, and socialist revolutions.<ref>{{pl icon}} J. Topolski, "Rewolucje w dziejach nowożytnych i najnowszych (xvii-xx wiek)," Kwartalnik Historyczny, LXXXIII, 1976, 251-67</ref> | There are many different typologies of revolutions in social science and literature. For example, classical scholar [[Alexis de Tocqueville]] differentiated<ref>Roger Boesche, ''Tocqueville's Road Map: Methodology, Liberalism, Revolution, and Despotism'', Lexington Books, 2006, ISBN 0739116657, [http://books.google.com/books?id=fLL6Bil2gtcC&pg=PA86&dq=%22types+of+revolution%22&as_brr=3&ei=hdVQR6TVIpm4pgLFvJ2fBw&sig=ZEc373JU8-9qM9N4BgKjnvvHVD8#PPA86,M1 Google Print, p.86]</ref> between 1) [[political revolution]]s 2) sudden and violent revolutions that seek not only to establish a new political system but to transform an entire society and 3) slow but sweeping transformations of the entire society that take several generations to bring about (ex. [[religion]]). One of several different [[Marxist]] typologies divides revolutions into pre-capitalist, early bourgeois, bourgeois, bourgeois-democratic, early proletarian, and socialist revolutions.<ref>{{pl icon}} J. Topolski, "Rewolucje w dziejach nowożytnych i najnowszych (xvii-xx wiek)," Kwartalnik Historyczny, LXXXIII, 1976, 251-67</ref> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 28: | ||

The term "revolution" has also been used to denote great changes outside the political sphere. Such revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed in [[society]], [[culture]], [[philosophy]] and [[technology]] much more than [[political system]]s; they are often known as [[social revolution]]s.<ref>Irving E. Fang, ''A History of Mass Communication: Six Information Revolutions'', Focal Press, 1997, ISBN 0240802543, [http://books.google.com/books?id=QaVfg_vdyxsC&dq=communication+technology+changed+business&as_brr=3&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0 Google Print, p. xv]</ref> Some can be global, while others are limited to single countries. One of the classic examples of the usage of the word revolution in such context is the [[industrial revolution]] (note that such revolutions also fit the "slow revolution" definition of Tocqueville).<ref>Warwick E. Murray, Routledge, 2006, ISBN 0415318009, [http://books.google.com/books?id=L-3Vq3aadTYC&pg=PA226&dq=%22cultural+revolutions%22&as_brr=3&ei=ddtQR5aHKovqoQLy7J2UAg&sig=Nrc0rBp_zg_44liln8OLNsUu7UE Google Print, p.226]</ref> | The term "revolution" has also been used to denote great changes outside the political sphere. Such revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed in [[society]], [[culture]], [[philosophy]] and [[technology]] much more than [[political system]]s; they are often known as [[social revolution]]s.<ref>Irving E. Fang, ''A History of Mass Communication: Six Information Revolutions'', Focal Press, 1997, ISBN 0240802543, [http://books.google.com/books?id=QaVfg_vdyxsC&dq=communication+technology+changed+business&as_brr=3&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0 Google Print, p. xv]</ref> Some can be global, while others are limited to single countries. One of the classic examples of the usage of the word revolution in such context is the [[industrial revolution]] (note that such revolutions also fit the "slow revolution" definition of Tocqueville).<ref>Warwick E. Murray, Routledge, 2006, ISBN 0415318009, [http://books.google.com/books?id=L-3Vq3aadTYC&pg=PA226&dq=%22cultural+revolutions%22&as_brr=3&ei=ddtQR5aHKovqoQLy7J2UAg&sig=Nrc0rBp_zg_44liln8OLNsUu7UE Google Print, p.226]</ref> | ||

== Dominion Body == | |||

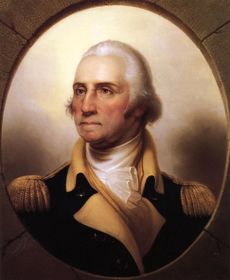

[[File:Portrait of George Washington.jpeg|thumb|upright|left|[[George Washington]], leader of the [[American Revolution]].]] | |||

TBS: my version of the body § I may hold this back pending update to current release of the mediawiki CMS. | |||

== English Wiki Body § as of 2011-10-19== | == English Wiki Body § as of 2011-10-19== | ||

:''This content represents the consensus neo-liberal world view as worked out to point at which I cloned my draft'' | |||

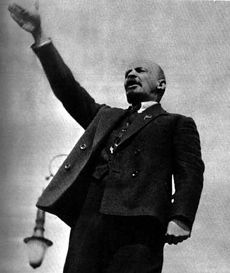

[[File:Lenin.WWI.JPG|thumb|upright| | [[File:Lenin.WWI.JPG|thumb|upright|right|[[Vladimir Lenin]], leader of the [[Bolshevik Revolution of 1917]].]] | ||

[[File:Sunyatsen1.jpg|thumb|upright|right|[[Sun Yat-sen]], leader of the Chinese [[Xinhai Revolution]] in 1911.]] | [[File:Sunyatsen1.jpg|thumb|upright|right|[[Sun Yat-sen]], leader of the Chinese [[Xinhai Revolution]] in 1911.]] | ||

| Line 46: | Line 56: | ||

The works of [[Ted Robert Gurr]], [[Ivo K. Feierbrand]], [[Rosalind L. Feierbrand]], [[James A. Geschwender]], [[David C. Schwartz]] and [[Denton E. Morrison]] fall into the first category. They followed theories of [[cognitive psychology]] and [[frustration-aggression theory]] and saw the cause of revolution in the state of mind of the masses, and while they varied in their approach as to what exactly caused the people to revolt (e.g. [[modernization]], [[recession]] or [[discrimination]]), they agreed that the primary cause for revolution was the widespread frustration with socio-political situation.<ref name="Goldstonet3"/> | The works of [[Ted Robert Gurr]], [[Ivo K. Feierbrand]], [[Rosalind L. Feierbrand]], [[James A. Geschwender]], [[David C. Schwartz]] and [[Denton E. Morrison]] fall into the first category. They followed theories of [[cognitive psychology]] and [[frustration-aggression theory]] and saw the cause of revolution in the state of mind of the masses, and while they varied in their approach as to what exactly caused the people to revolt (e.g. [[modernization]], [[recession]] or [[discrimination]]), they agreed that the primary cause for revolution was the widespread frustration with socio-political situation.<ref name="Goldstonet3"/> | ||

The second group, composed of academics such as [[Chalmers Johnson]], [[Neil Smelser]], [[Bob Jessop]], [[Mark Hart]], [[Edward A. Tiryakian]], [[Mark Hagopian]], followed in the footsteps of [[Talcott Parsons]] and the [[structural-functionalist]] theory in sociology; they saw society as a system in equilibrium between various resources, demands and subsystems (political, cultural, etc.). As in the psychological school, they differed in their definitions of what causes disequilibrium, but agreed that it is a state of a severe disequilibrium that is responsible for revolutions.<ref name="Goldstonet3"/> | The second group, composed of academics such as [[Chalmers Johnson]], [[Neil Smelser]], [[Bob Jessop]], [[Mark Hart]], [[Edward A. Tiryakian]], [[Mark Hagopian]], followed in the footsteps of [[Talcott Parsons]] and the [[structural-functionalist]] theory in sociology; they saw society as a system in equilibrium between various resources, demands and subsystems (political, cultural, etc.). As in the psychological school, they differed in their definitions of what causes disequilibrium, but agreed that it is a state of a severe disequilibrium that is responsible for revolutions.<ref name="Goldstonet3"/> | ||

| Line 58: | Line 67: | ||

The criticism of the second generation led to the rise of a third generation of theories, with writers such as [[Theda Skocpol]], [[Barrington Moore]], [[Jeffrey Paige]] and others expanding on the old [[Marxism|Marxist]] [[class conflict]] approach, turning their attention to rural agrarian-state conflicts, state conflicts with autonomous [[elites]] and the impact of interstate [[economic]] and [[military]] competition on domestic [[political change]]. Particularly Skocpol's ''[[States and Social Revolutions]]'' became one of the most widely recognized works of the third generation; Skocpol defined revolution as "rapid, basic transformations of society's state and class structures...accompanied and in part carried through by class-based revolts from below", attributing revolutions to a conjunction of multiple conflicts involving state, elites and the lower classes.<ref name="Goldstonet4"/> | The criticism of the second generation led to the rise of a third generation of theories, with writers such as [[Theda Skocpol]], [[Barrington Moore]], [[Jeffrey Paige]] and others expanding on the old [[Marxism|Marxist]] [[class conflict]] approach, turning their attention to rural agrarian-state conflicts, state conflicts with autonomous [[elites]] and the impact of interstate [[economic]] and [[military]] competition on domestic [[political change]]. Particularly Skocpol's ''[[States and Social Revolutions]]'' became one of the most widely recognized works of the third generation; Skocpol defined revolution as "rapid, basic transformations of society's state and class structures...accompanied and in part carried through by class-based revolts from below", attributing revolutions to a conjunction of multiple conflicts involving state, elites and the lower classes.<ref name="Goldstonet4"/> | ||

[[File:Thefalloftheberlinwall1989.JPG|thumb|left|The fall of the [[Berlin Wall]] and most of the events of the [[Autumn of Nations]] in Europe, 1989, were sudden and peaceful.]] | |||

[[File:Freedom Square Baku 1990.jpg|thumb|The rebirth of the [[Azerbaijan]] Republic as people gather at [[Azadliq Square, Baku|Azadlyg Square]], shortly after [[Black January]].]] | [[File:Freedom Square Baku 1990.jpg|thumb|The rebirth of the [[Azerbaijan]] Republic as people gather at [[Azadliq Square, Baku|Azadlyg Square]], shortly after [[Black January]].]] | ||

From the late 1980s a new body of scholarly work began questioning the dominance of the third generation's theories. The old theories were also dealt a significant blow by new revolutionary events that could not be easily explain by them. The [[Iranian Revolution|Iranian]] and [[Nicaraguan Revolution]]s of 1979, the [[1986]] [[People Power Revolution]] in the [[Philippines]] and the 1989 [[Autumn of Nations]] in Europe saw multi-class coalitions topple seemingly powerful regimes amidst popular demonstrations and [[General strike|mass strikes]] in [[nonviolent revolution]]s. | From the late 1980s a new body of scholarly work began questioning the dominance of the third generation's theories. The old theories were also dealt a significant blow by new revolutionary events that could not be easily explain by them. The [[Iranian Revolution|Iranian]] and [[Nicaraguan Revolution]]s of 1979, the [[1986]] [[People Power Revolution]] in the [[Philippines]] and the 1989 [[Autumn of Nations]] in Europe saw multi-class coalitions topple seemingly powerful regimes amidst popular demonstrations and [[General strike|mass strikes]] in [[nonviolent revolution]]s. | ||

| Line 98: | Line 108: | ||

* [http://www.dailyevergreen.com/story/29050 DailyEvergreen.com], Vive la Révolution!: Revolution is an Indelible Phenomenon Throughout History by Qasim Hussaini | * [http://www.dailyevergreen.com/story/29050 DailyEvergreen.com], Vive la Révolution!: Revolution is an Indelible Phenomenon Throughout History by Qasim Hussaini | ||

* [http://www.marxists.org/archive/mandel/1989/xx/rev-today.htm Ernest Mandel, "The Marxist Case for Revolution Today", 1989] | * [http://www.marxists.org/archive/mandel/1989/xx/rev-today.htm Ernest Mandel, "The Marxist Case for Revolution Today", 1989] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:17, 22 November 2011

A revolution (from the Latin revolutio, "a turn around") is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time. Aristotle described two types of political revolution:

- Complete change from one constitution to another

- Modification of an existing constitution.[1]

Scholarly debates about what does and does not constitute a revolution center around several issues. Early studies of revolutions primarily analyzed events in European history from a psychological perspective, but more modern examinations include global events and incorporate perspectives from several social sciences, including sociology and political science. Several generations of scholarly thought on revolutions have generated many competing theories and contributed much to the current understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Etymology

Copernicus named his 1543 treatise on the movements of planets around the sun De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of Celestial Bodies) and this has come to be the model type of a scientific revolution. However "Revolution" is attested by at least 1450 in the sense of representing abrupt change in a social order[2][3]. Political usage of the term had been well established by 1688 in the description of the replacement of James II with William III. The process was termed "The Glorious Revolution".[4] Apparently the sense of social change and the geometric sense as in "Surface of revolution" developed in various European languages from the Latin between the 14th and 17th centuries, the former developing as a metaphor from the latter. "Revolt" as an event designation appears after the process term and is given a related but distinct and later derivation.

Types

There are many different typologies of revolutions in social science and literature. For example, classical scholar Alexis de Tocqueville differentiated[5] between 1) political revolutions 2) sudden and violent revolutions that seek not only to establish a new political system but to transform an entire society and 3) slow but sweeping transformations of the entire society that take several generations to bring about (ex. religion). One of several different Marxist typologies divides revolutions into pre-capitalist, early bourgeois, bourgeois, bourgeois-democratic, early proletarian, and socialist revolutions.[6]

Charles Tilly, a modern scholar of revolutions, differentiated[7] between a coup, a top-down seizure of power, a civil war, a revolt and a "great revolution" (revolutions that transform economic and social structures as well as political institutions, such as the French Revolution of 1789, Russian Revolution of 1917, or Islamic Revolution of Iran).[8]

Other types of revolution, created for other typologies, include the social revolutions; proletarian or communist revolutions inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aims to replace capitalism with communism); failed or abortive revolutions (revolutions that fail to secure power after temporary victories or large-scale mobilization) or violent vs. nonviolent revolutions.

The term "revolution" has also been used to denote great changes outside the political sphere. Such revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed in society, culture, philosophy and technology much more than political systems; they are often known as social revolutions.[9] Some can be global, while others are limited to single countries. One of the classic examples of the usage of the word revolution in such context is the industrial revolution (note that such revolutions also fit the "slow revolution" definition of Tocqueville).[10]

Dominion Body

TBS: my version of the body § I may hold this back pending update to current release of the mediawiki CMS.

English Wiki Body § as of 2011-10-19

- This content represents the consensus neo-liberal world view as worked out to point at which I cloned my draft

Perhaps most often, the word 'revolution' is employed to denote a change in socio-political institutions.[11][12][13] Jeff Goodwin gives two definitions of a revolution. A broad one, where revolution is

| “ | "any and all instances in which a state or a political regime is overthrown and thereby transformed by a popular movement in an irregular, extraconstitutional and/or violent fashion" | ” |

and a narrow one, in which

| “ | "revolutions entail not only mass mobilization and regime change, but also more or less rapid and fundamental social, economic and/or cultural change, during or soon after the struggle for state power."[14] | ” |

Jack Goldstone defines them as

| “ | "an effort to transform the political institutions and the justifications for political authority in society, accompanied by formal or informal mass mobilization and noninstitutionalized actions that undermine authorities."[15] | ” |

Political and socioeconomic revolutions have been studied in many social sciences, particularly sociology, political sciences and history. Among the leading scholars in that area have been or are Crane Brinton, Charles Brockett, Farideh Farhi, John Foran, John Mason Hart, Samuel Huntington, Jack Goldstone, Jeff Goodwin, Ted Roberts Gurr, Fred Halliday, Chalmers Johnson, Tim McDaniel, Barrington Moore, Jeffery Paige, Vilfredo Pareto, Terence Ranger, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, Theda Skocpol, James Scott, Eric Selbin, Charles Tilly, Ellen Kay Trimbringer, Carlos Vistas, John Walton, Timothy Wickham-Crowley and Eric Wolf.[16]

Scholars of revolutions, like Jack Goldstone, differentiate four current 'generations' of scholarly research dealing with revolutions.[15] The scholars of the first generation such as Gustave Le Bon, Charles A. Ellwood or Pitirim Sorokin, were mainly descriptive in their approach, and their explanations of the phenomena of revolutions was usually related to social psychology, such as Le Bon's crowd psychology theory.[11]

Second generation theorists sought to develop detailed theories of why and when revolutions arise, grounded in more complex social behavior theories. They can be divided into three major approaches: psychological, sociological and political.[11]

The works of Ted Robert Gurr, Ivo K. Feierbrand, Rosalind L. Feierbrand, James A. Geschwender, David C. Schwartz and Denton E. Morrison fall into the first category. They followed theories of cognitive psychology and frustration-aggression theory and saw the cause of revolution in the state of mind of the masses, and while they varied in their approach as to what exactly caused the people to revolt (e.g. modernization, recession or discrimination), they agreed that the primary cause for revolution was the widespread frustration with socio-political situation.[11]

The second group, composed of academics such as Chalmers Johnson, Neil Smelser, Bob Jessop, Mark Hart, Edward A. Tiryakian, Mark Hagopian, followed in the footsteps of Talcott Parsons and the structural-functionalist theory in sociology; they saw society as a system in equilibrium between various resources, demands and subsystems (political, cultural, etc.). As in the psychological school, they differed in their definitions of what causes disequilibrium, but agreed that it is a state of a severe disequilibrium that is responsible for revolutions.[11]

Finally, the third group, which included writers such as Charles Tilly, Samuel P. Huntington, Peter Ammann and Arthur L. Stinchcombe followed the path of political sciences and looked at pluralist theory and interest group conflict theory. Those theories see events as outcomes of a power struggle between competing interest groups. In such a model, revolutions happen when two or more groups cannot come to terms within a normal decision making process traditional for a given political system, and simultaneously have enough resources to employ force in pursuing their goals.[11]

The second generation theorists saw the development of the revolutions as a two-step process; first, some change results in the present situation being different from the past; second, the new situation creates an opportunity for a revolution to occur. In that situation, an event that in the past would not be sufficient to cause a revolution (ex. a war, a riot, a bad harvest), now is sufficient – however if authorities are aware of the danger, they can still prevent a revolution (through reform or repression).[15]

Many such early studies of revolutions tended to concentrate on four classic cases—famous and uncontroversial examples that fit virtually all definitions of revolutions, like the Glorious Revolution (1688), the French Revolution (1789–1799), the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Chinese Revolution (1927–1949).[15] In his famous "The Anatomy of Revolution", however, the eminent Harvard historian, Crane Brinton, focused on the English Civil War, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Russian Revolution.[17]

In time, scholars began to analyze hundreds of other events as revolutions (see list of revolutions and rebellions), and differences in definitions and approaches gave rise to new definitions and explanations. The theories of the second generation have been criticized for their limited geographical scope, difficulty in empirical verification, as well as that while they may explain some particular revolutions, they did not explain why revolutions did not occur in other societies in very similar situations.[15]

The criticism of the second generation led to the rise of a third generation of theories, with writers such as Theda Skocpol, Barrington Moore, Jeffrey Paige and others expanding on the old Marxist class conflict approach, turning their attention to rural agrarian-state conflicts, state conflicts with autonomous elites and the impact of interstate economic and military competition on domestic political change. Particularly Skocpol's States and Social Revolutions became one of the most widely recognized works of the third generation; Skocpol defined revolution as "rapid, basic transformations of society's state and class structures...accompanied and in part carried through by class-based revolts from below", attributing revolutions to a conjunction of multiple conflicts involving state, elites and the lower classes.[15]

From the late 1980s a new body of scholarly work began questioning the dominance of the third generation's theories. The old theories were also dealt a significant blow by new revolutionary events that could not be easily explain by them. The Iranian and Nicaraguan Revolutions of 1979, the 1986 People Power Revolution in the Philippines and the 1989 Autumn of Nations in Europe saw multi-class coalitions topple seemingly powerful regimes amidst popular demonstrations and mass strikes in nonviolent revolutions.

Defining revolutions as mostly European violent state versus people and class struggles conflicts was no longer sufficient. The study of revolutions thus evolved in three directions, firstly, some researchers were applying previous or updated structuralist theories of revolutions to events beyond the previously analyzed, mostly European conflicts. Secondly, scholars called for greater attention to conscious agency in the form of ideology and culture in shaping revolutionary mobilization and objectives. Third, analysts of both revolutions and social movements realized that those phenomena have much in common, and a new 'fourth generation' literature on contentious politics has developed that attempts to combine insights from the study of social movements and revolutions in hopes of understanding both phenomena.[15]

While revolutions encompass events ranging from the relatively peaceful revolutions that overthrew communist regimes to the violent Islamic revolution in Afghanistan, they exclude coups d'états, civil wars, revolts and rebellions that make no effort to transform institutions or the justification for authority (such as Józef Piłsudski's May Coup of 1926 or the American Civil War), as well as peaceful transitions to democracy through institutional arrangements such as plebiscites and free elections, as in Spain after the death of Francisco Franco.[15]

Lists of revolutions

For a list of revolutions see:

See also

References

- ↑ Aristotle, The Politics V, tr. T.A. Sinclair (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964, 1972), p. 190.

- ↑ OED vol Q-R p. 617 1979 Sense III states a usage "Alteration, change, mutation" from 1400 but lists it as "rare". "c. 1450, Lydg 1196 Secrees of Elementys the Revoluciuons, Chaung of tymes and Complexiouns." It's clear that the usage had been established by the early 15th century but only came into common use in the late 17th in England.

- ↑ onlineetymology.com

- ↑ Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution

- ↑ Roger Boesche, Tocqueville's Road Map: Methodology, Liberalism, Revolution, and Despotism, Lexington Books, 2006, ISBN 0739116657, Google Print, p.86

- ↑ Template:Language icon J. Topolski, "Rewolucje w dziejach nowożytnych i najnowszych (xvii-xx wiek)," Kwartalnik Historyczny, LXXXIII, 1976, 251-67

- ↑ Charles Tilly, ''European Revolutions, 1492-1992, Blackwell Publishing, 1995, ISBN 0631199039, Google Print, p.16

- ↑ Bernard Lewis, "Iran in History", Moshe Dayan Center, Tel Aviv University

- ↑ Irving E. Fang, A History of Mass Communication: Six Information Revolutions, Focal Press, 1997, ISBN 0240802543, Google Print, p. xv

- ↑ Warwick E. Murray, Routledge, 2006, ISBN 0415318009, Google Print, p.226

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Jack Goldstone, "Theories of Revolutions: The Third Generation, World Politics 32, 1980:425-53

- ↑ John Foran, "Theories of Revolution Revisited: Toward a Fourth Generation", Sociological Theory 11, 1993:1-20

- ↑ Clifton B. Kroeber, Theory and History of Revolution, Journal of World History 7.1, 1996: 21-40

- ↑ Goodwin, p.9.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Jack Goldstone, "Towards a Fourth Generation of Revolutionary Theory", Annual Review of Political Science 4, 2001:139-87

- ↑ Jeff Goodwin, No Other Way Out: States and Revolutionary Movements, 1945-1991. Cambridge University Press, 2001, p.5

- ↑ Crane Brinton, The Anatomy of Revolution, revised ed. (New York, Vintage Books, 1965). First edition, 1938.

Bibliography

- The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, ed. by Immanuel Ness, Malden, MA [etc.]: Wiley & Sons, 2009, ISBN 1405184647

- Perreau-Sausine, Emile, Les libéraux face aux révolutions : 1688, 1789, 1917, 1933, Commentaire, Spring 2005, pp. 181–193

External links

- Hannah Arendt, IEP.UTM.edu, On Revolution, 1963, Penguin Classics, New Ed edition: February 8, 1991. ISBN 014018421X

- Daemon.be, Revolution in Political Risk Management

- John Kekes, City-Journal.org Why Robespierre Chose Terror. The lessons of the first totalitarian revolution, City Journal, Spring 2006.

- Plinio Correa de Oliveira, TFP.org, Revolution and Counter-Revolution, Foundation for a Christian, Third edition, 1993. ISBN 1877905275

- Michael Barken, ZMAG.org, Regulating revolutions in Eastern Europe: Polyarchy and the National Endowment for Democracy, 1 November 2006.

- Polyarchy.org, Polyarchy Documents: Revolution

- DailyEvergreen.com, Vive la Révolution!: Revolution is an Indelible Phenomenon Throughout History by Qasim Hussaini

- Ernest Mandel, "The Marxist Case for Revolution Today", 1989